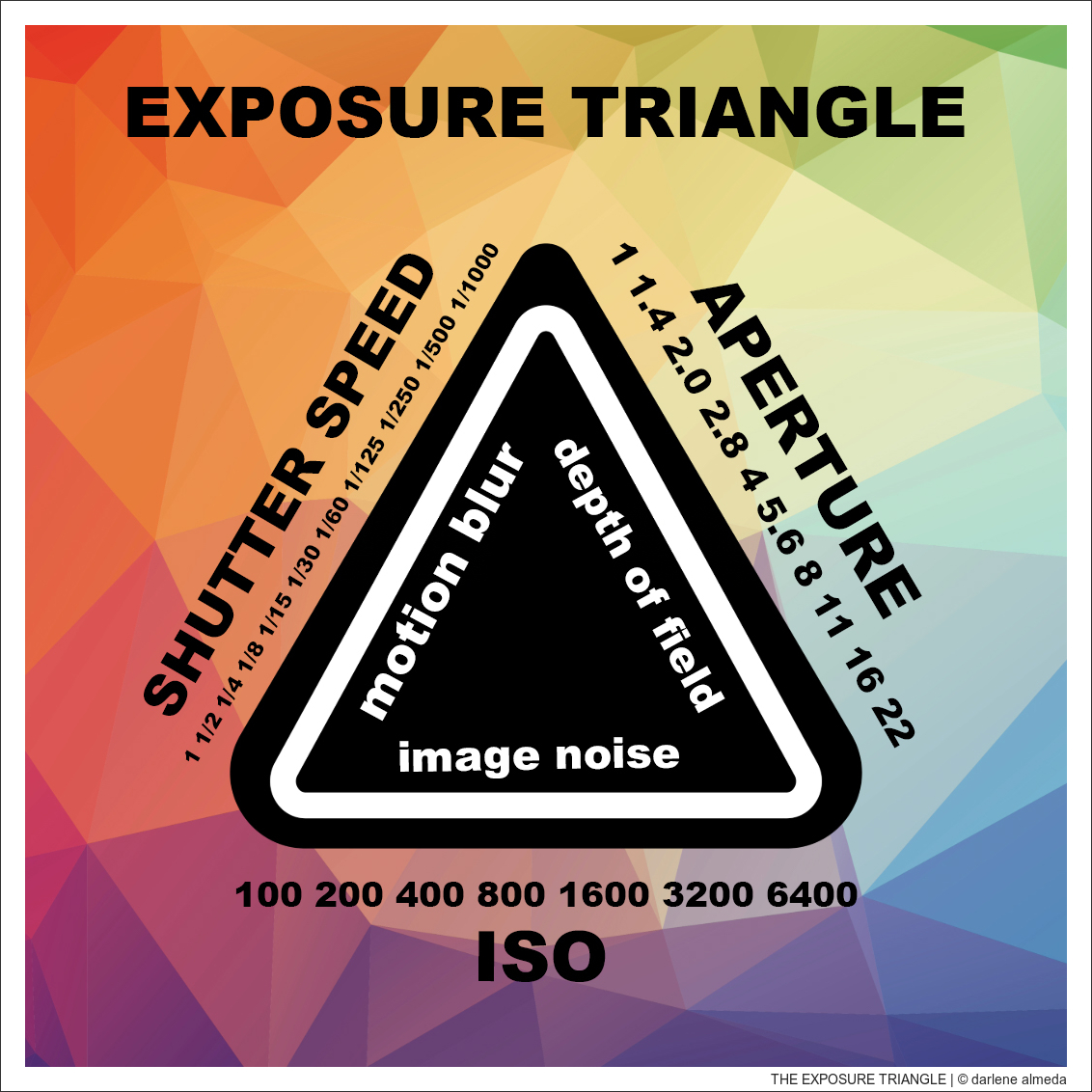

Most people respond to color first. It’s immediate and emotional, and it often feels like the thing that makes a photograph work. But color can also distract us from what a photograph is really built on: light, shape, and value.

In this second part of Lighting 101, the focus shifts away from color and toward seeing light more clearly by paying attention to how it shapes form and creates value. However, before removing color, it helps to understand where the light was placed. The images below were made with the same subject and background, with only the position of the light changing slightly.

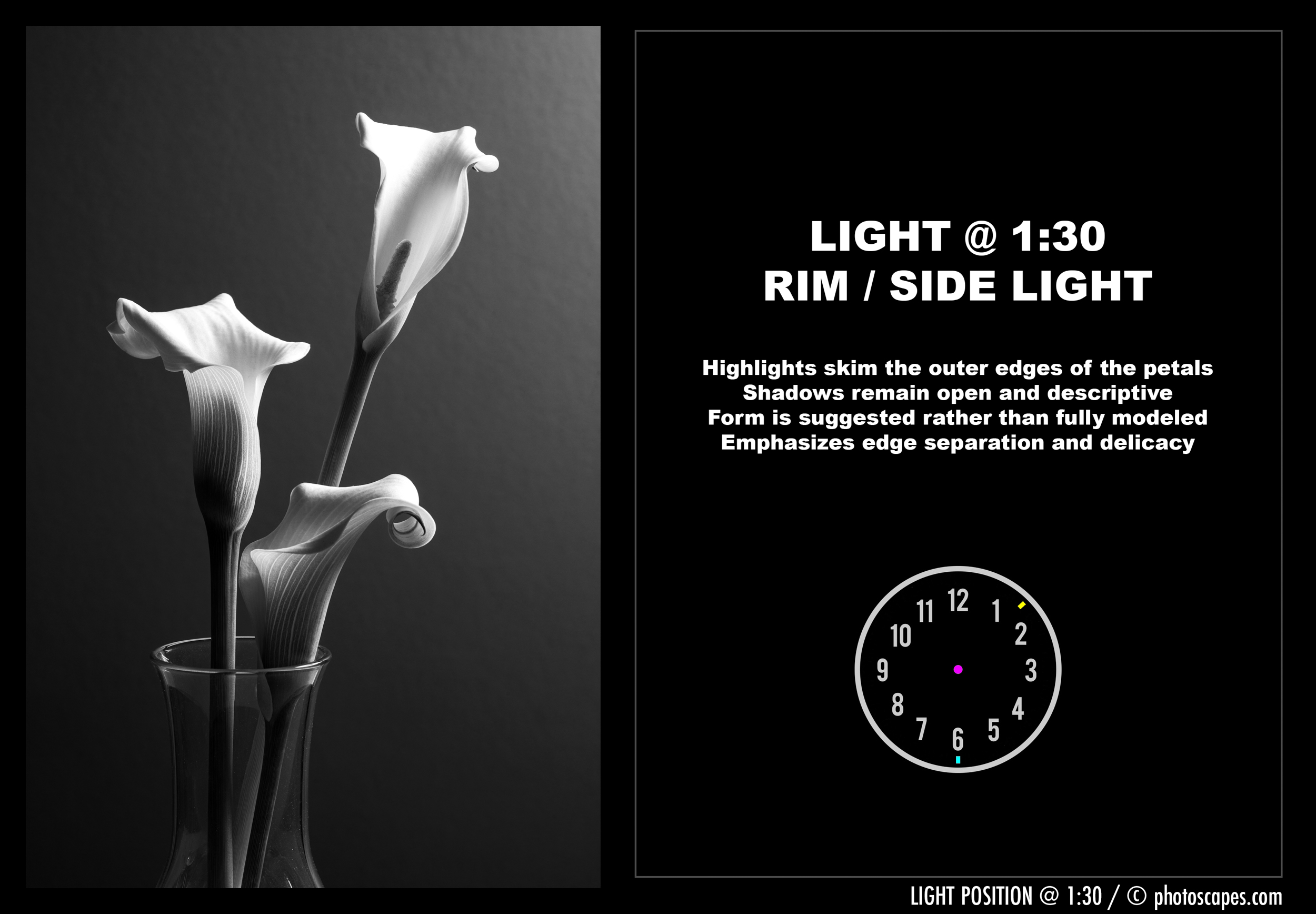

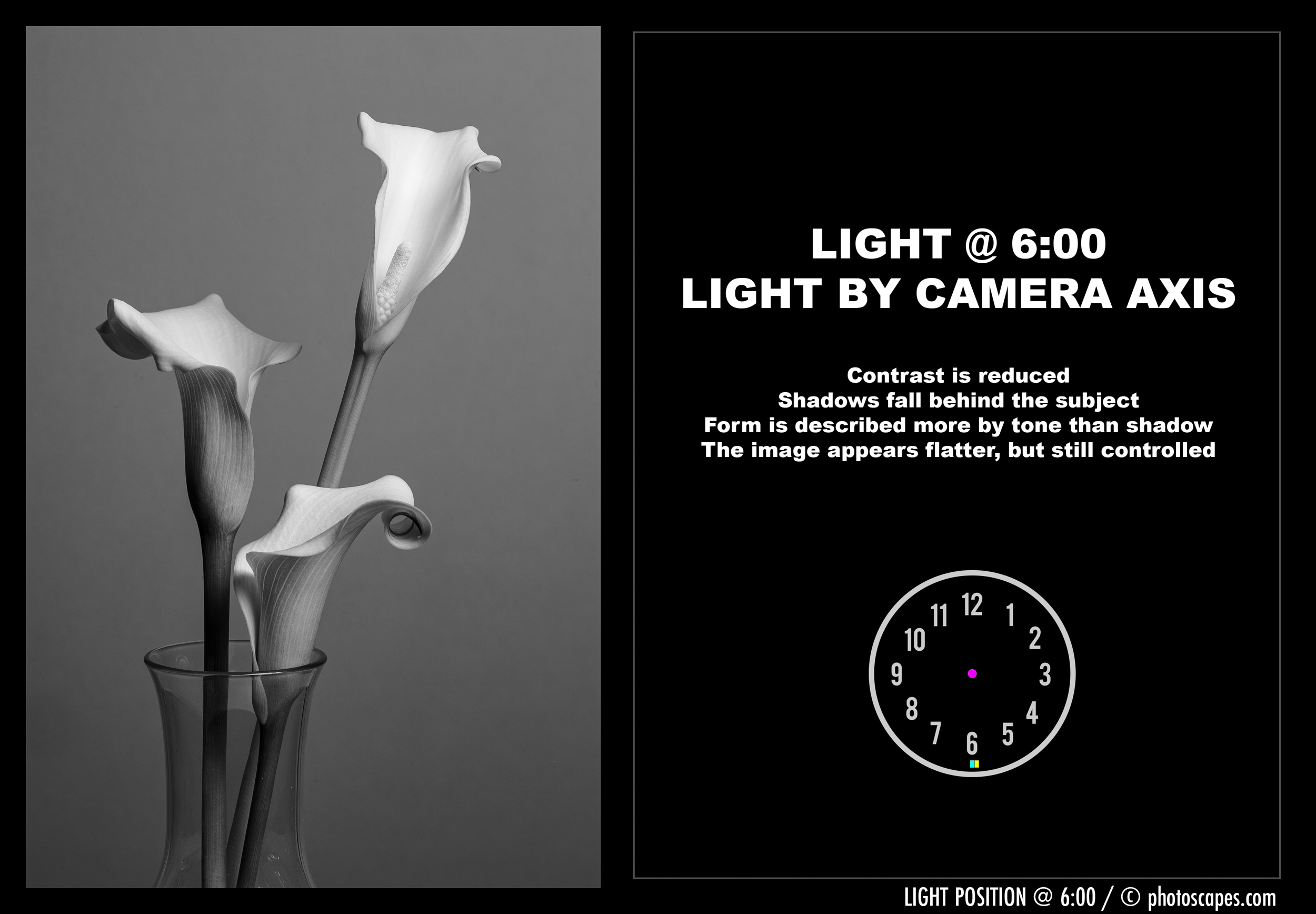

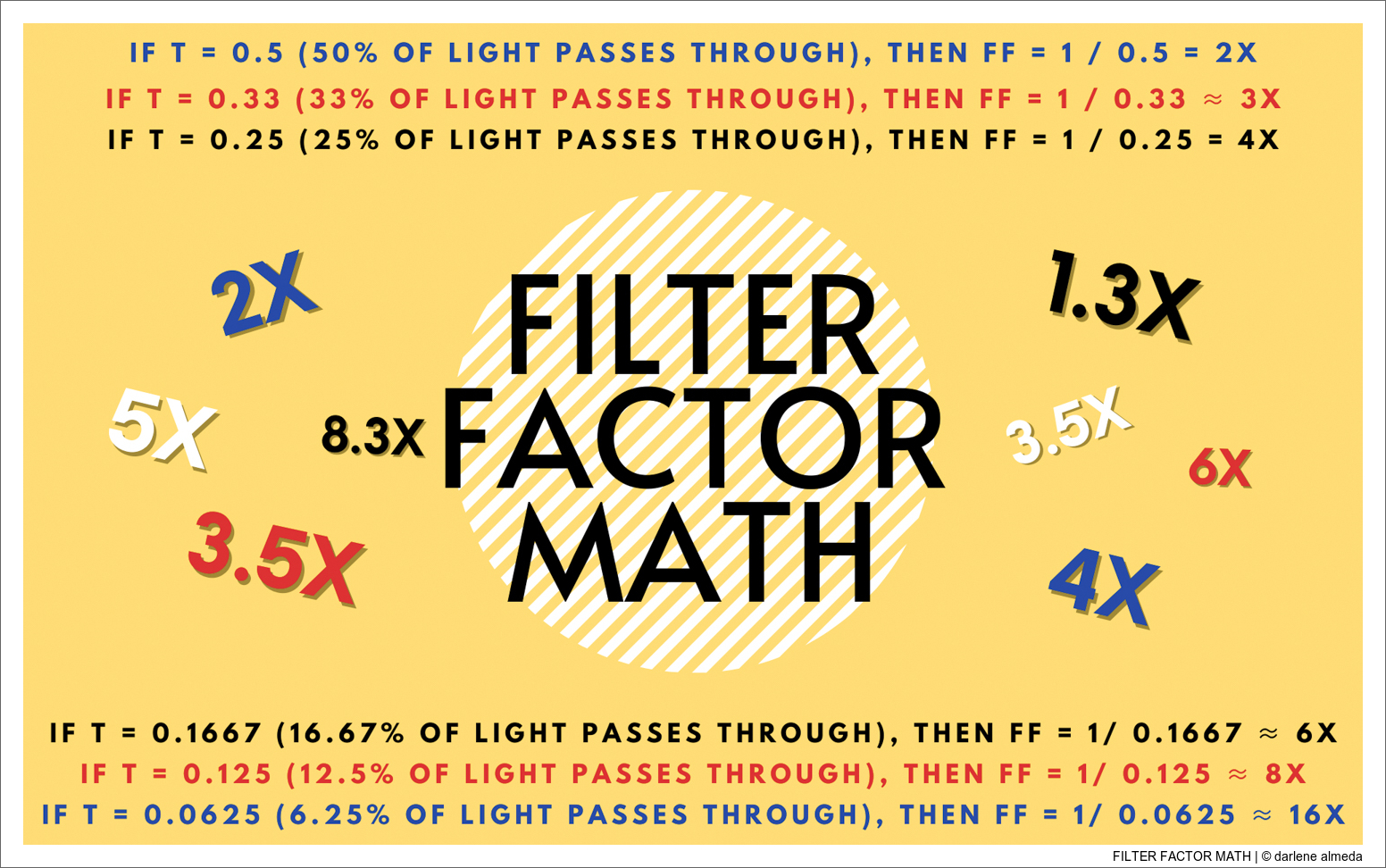

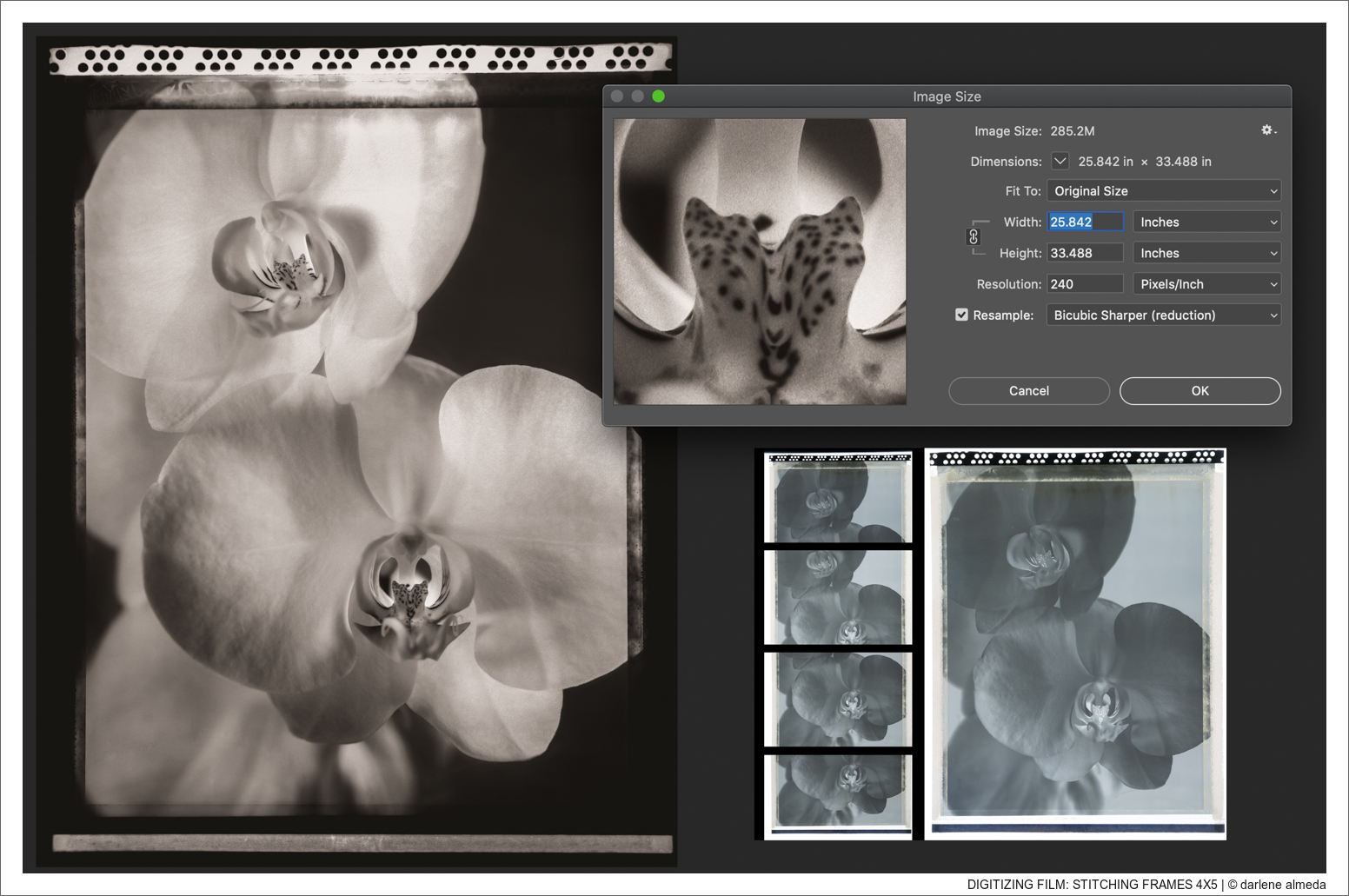

In the sequence of images above, the light was moved to various positions in relation to the flowers. Rather than getting into angle measurements, I prefer to describe the light’s position using the face of an analog clock—a simple, intuitive reference most of us already understand.

Moving Light Direction

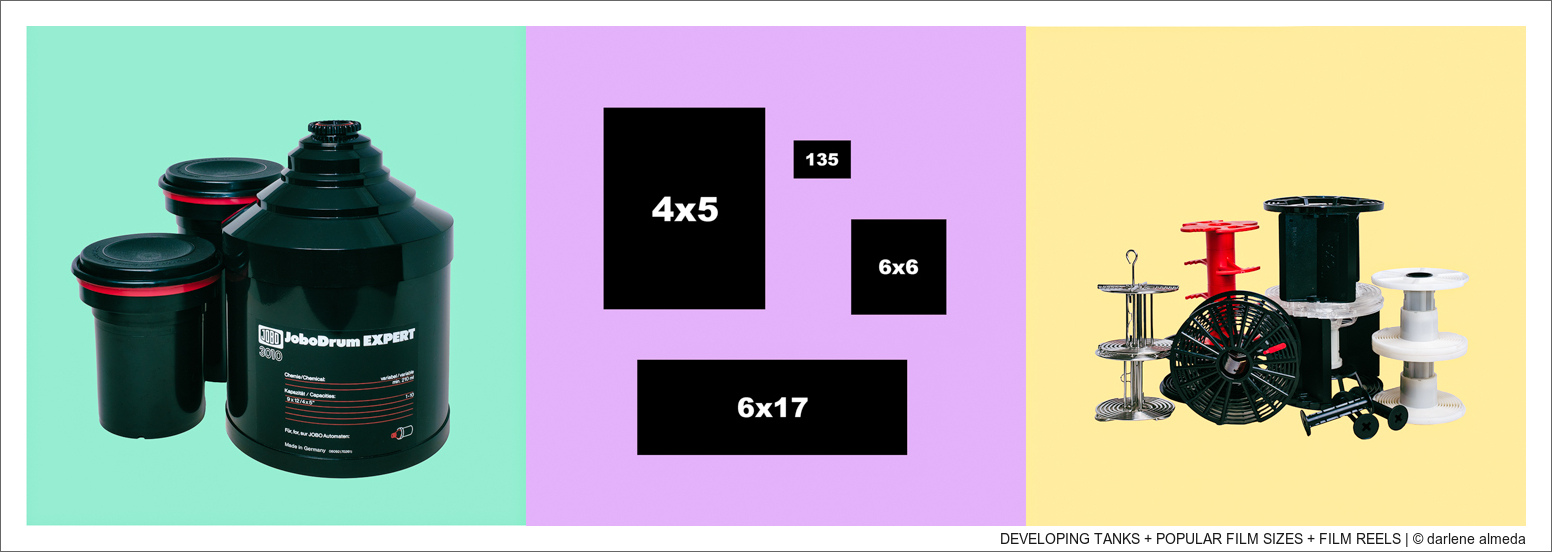

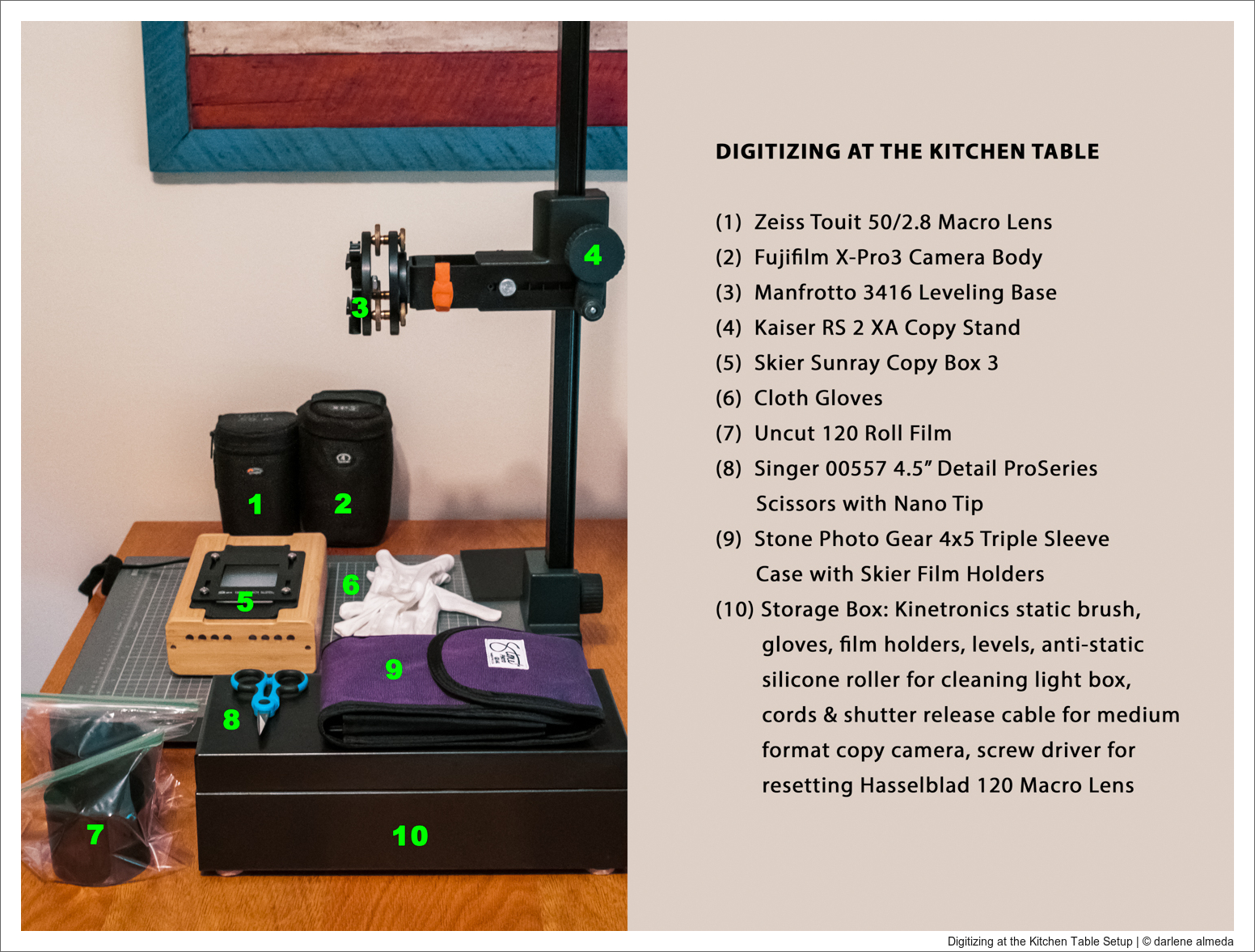

You can see the simple setup above: a gray mat board for the backdrop, a small shooting table, and a single light on a wheeled light stand. I highly recommend trying a setup like this. There’s no need for an expensive strobe—hardware stores sell inexpensive clamp lights that work perfectly well for exercises like this.

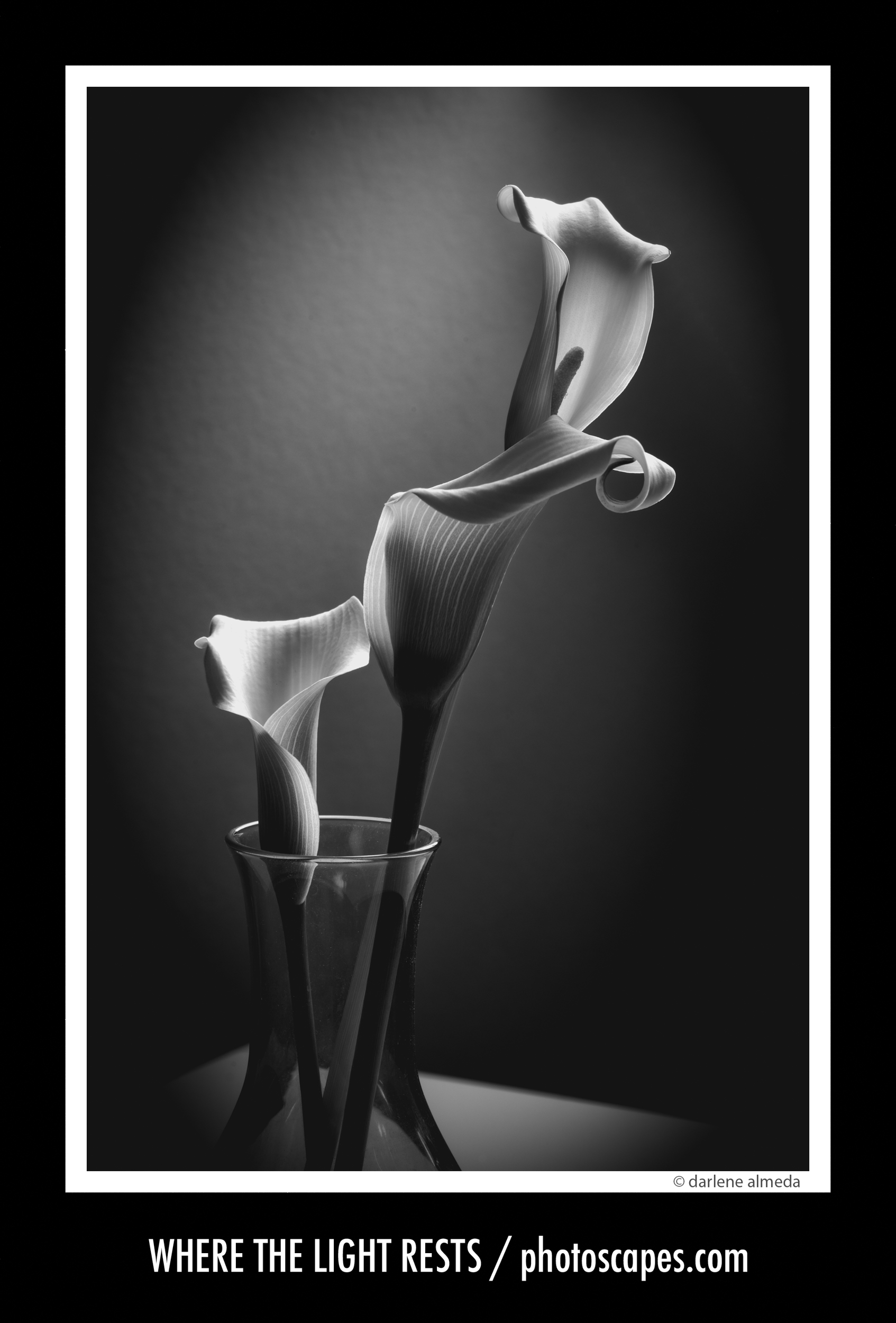

In the end, the goal is to study the results in black and white, where the behavior of the light becomes easier to see.

Below is the sequence of images in black and white. The clock positions show where the light is placed around the subject, which remains centered, while the camera stays fixed at approximately six o’clock.

Light Position @ 1:30

Light Position @ 3:00

Light Position @ 6:00

Moving the light closer to the camera axis produces a very different result.

Light Position @ 4:30

By this point, the light no longer needs explanation. Its placement and direction are visible in the way forms turn, overlap, and separate from the background. When light is placed with intention, shape and value carry the photograph, and color becomes optional.

This is the foundation—everything else builds from here. Shape and value are just the beginning. The next step is understanding how light direction affects those qualities, and how moving a single light changes the way form is described.

for you, for me, the whole world

this festive season