It’s time to take a short break from the technical talk and have a little fun—just shooting with natural light.

While I genuinely enjoy sharing techniques and lessons learned along the way, it’s just as important to step back and play. I’ve always believed learning works best when we do more than dip our toes in the water. Sometimes you have to climb the tree, choose the branch that feels right, and take the leap into the swimming hole below.

So let’s take some of what we’ve covered in Lessons 1 through 8 and gently test the waters—no pressure, no measuring tape required.

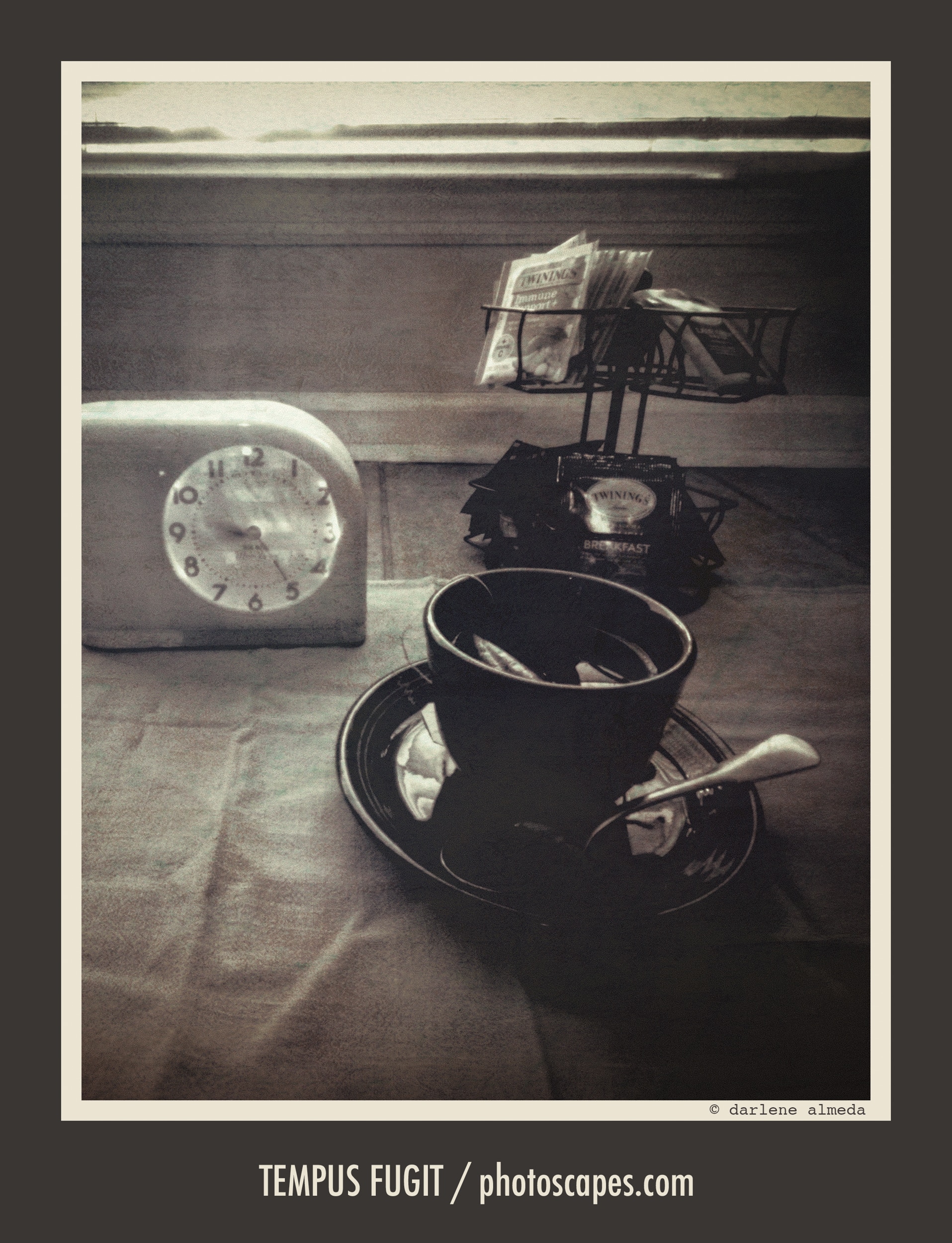

But first, I want to introduce an object that has stayed close to my photographic heart over the years, because it’s where my understanding of light truly began.

A Chair

For anyone who hasn’t read some of my earlier posts, let me introduce you to a very important tool from my photographic beginnings: a chair.

Not a throne.

Not the head of the art department.

Just a wonderfully ordinary chair—portable, dependable, and perfectly content to sit still.

This was the gear that taught me how to see light.

When I discovered my first chair, I was an art student studying illustration and graphic design. My days were packed—working during the day, school at night—and layered on top of that was the New York subway commute from Brooklyn to Manhattan and back. Some nights I didn’t get home until 11 p.m. It’s not something I’d rush to do again.

That said, I wasn’t too frightened. I was carrying a large portfolio case and an impressive assortment of graphic tools—X-Acto knives included—which probably gave me a false sense of invincibility. Still, I earned whatever came later.

I’m not afraid of hard work—though it often only looks heroic in hindsight. Life has a way of doing that.

After spending so much time learning how to make money as a commercial artist, something quietly dawned on me one day: what I was truly drawn to wasn’t the tools, or the layouts, or even the finished work.

It was light.

You can read books, or you can roll up your sleeves and teach yourself. In my experience, the people who really learn it… teach themselves.

I taught myself how to see light using a simple kitchen chair as my studio, and a large, beautiful window as my main light. In the late afternoons, that window would spill glorious light across the chair—and I paid attention.

The chair was portable, so I could move it easily—nudging it this way or that to catch the light just right. I also discovered that the small handheld mirror I used to check my hair could redirect light beautifully, as long as it was placed opposite the light source. From there, it became clear that I could bounce light even further, using additional mirrors or small pieces of cardboard wrapped in tin foil.

And just like that, I was in business.

The Misrepresentation of Gear

Having reliable gear is a fortunate thing in itself. I own more gear than I truly need, but as a former commercial photographer, that accumulation makes sense.

Once I find a system I genuinely love, I tend to stick with it. I’m not much for chasing the next thing. I also dislike selling gear—not because I can’t let it go, but because I have zero interest in playing salesperson. So yes, it accumulates.

So here’s my take on gear: when it comes to learning, less really is more.

Photography is about creating an image using light.

Great photography is about strong composition and beautiful light.

If you study art, you strengthen your creative eye.

If you study light—by actually working with it—you begin to understand and shape it.

Get yourself a chair.

Find a window or a door where light spills in.

And start studying what it does.

This doesn’t cost much money. Use whatever camera you already have—ideally digital—so you don’t have to wait on film processing to see what’s happening.

Use tablecloths as backdrops. Or better yet, visit a fabric store and buy a few yards of something simple. I used long skirts back in the day. Towels work just fine, too.

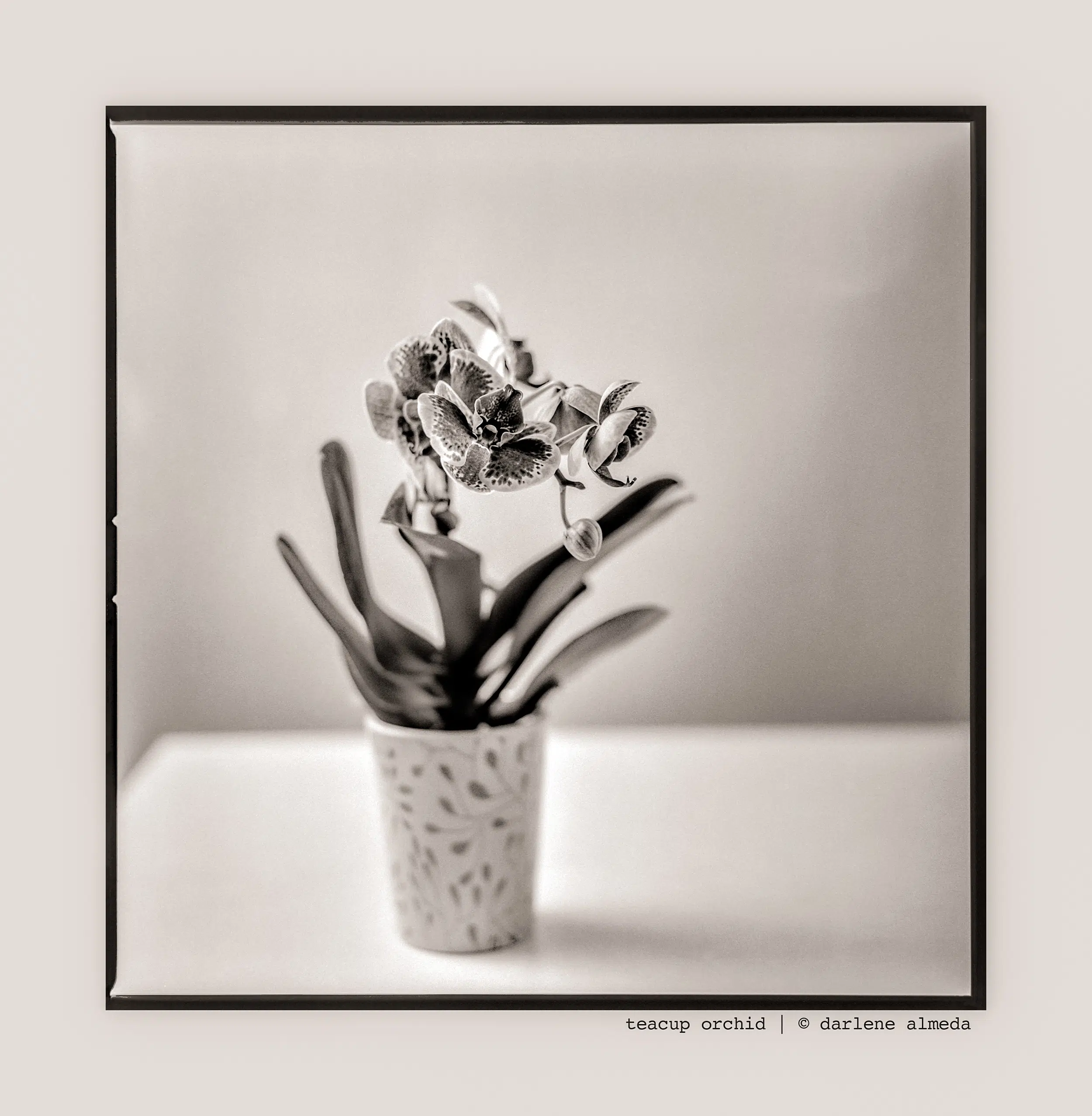

Choose small, ordinary objects—seashells, teacups, spools of thread, apples, spoons—anything that lets you observe how light behaves as it moves, shifts, softens, or hardens.

Keep a small mirror handy so you can bounce light back into the scene where you want it to go.

Behind The Scenes: Three Siblings on a Chair

Three Siblings on a Chair came together very quickly. It had been a full day. I’d just returned from a long drive after visiting an animal rescue I’m connected with, hauling over some heavy items for their fundraising efforts. By the time I walked back into the studio, I was tired—but then I noticed the light streaming in through the door.

That stopped me.

I remembered I wanted to write a post about The Chair, and it was already Thursday (I try to post on Fridays). The three robot siblings were sitting on a product table, and I knew I didn’t have much time. The sun was going to drop behind the trees in about thirty minutes.

So I moved fast.

I grabbed a kitchen chair, some background cloth I’d torn off a collapsible frame years ago, my camera, and a mirror mounted on a stand. The mirror, by the way, is a little warped from the time I placed it too close to a hot light (whoops). I keep it around anyway—it’s earned its place.

I do apologize for not capturing behind-the-scenes images before the shoot. Once the light disappears, so does the magic—and it’s hard to show something that no longer exists.

One thing worth noting: whenever I do a portrait—human or robotic (LOL)—it’s important to me that the eyes meet the viewer. That meant getting very low with the tripod so their gaze aligned just right.

I always use a tripod…

Unless the Rolling Stones are playing and I’m dancing during a product shoot.

When I look at Three Siblings on a Chair staring back at me, I laugh—because I do have three siblings. I’m number three out of four. The middle child.

The curious one,

the observant one,

the one who always seemed comfortable in the middle of things.

And maybe that’s what this image is really about.

Not robots.

Not props.

Not gear.

But noticing what’s already there.

Recognizing light when it appears.

And choosing—quietly—what it should say.

That choice is where lighting begins to matter.

So where do we go from here?

We’ll keep working with ordinary light, but we’ll start paying closer attention to the decisions we make with it. Not how much light we use, or where it comes from, but why we let it fall where it does.

Because seeing light is only the first step.

Choosing it is the next.

We keep it simple.

We keep watching the light.

And we keep showing up—chair ready.