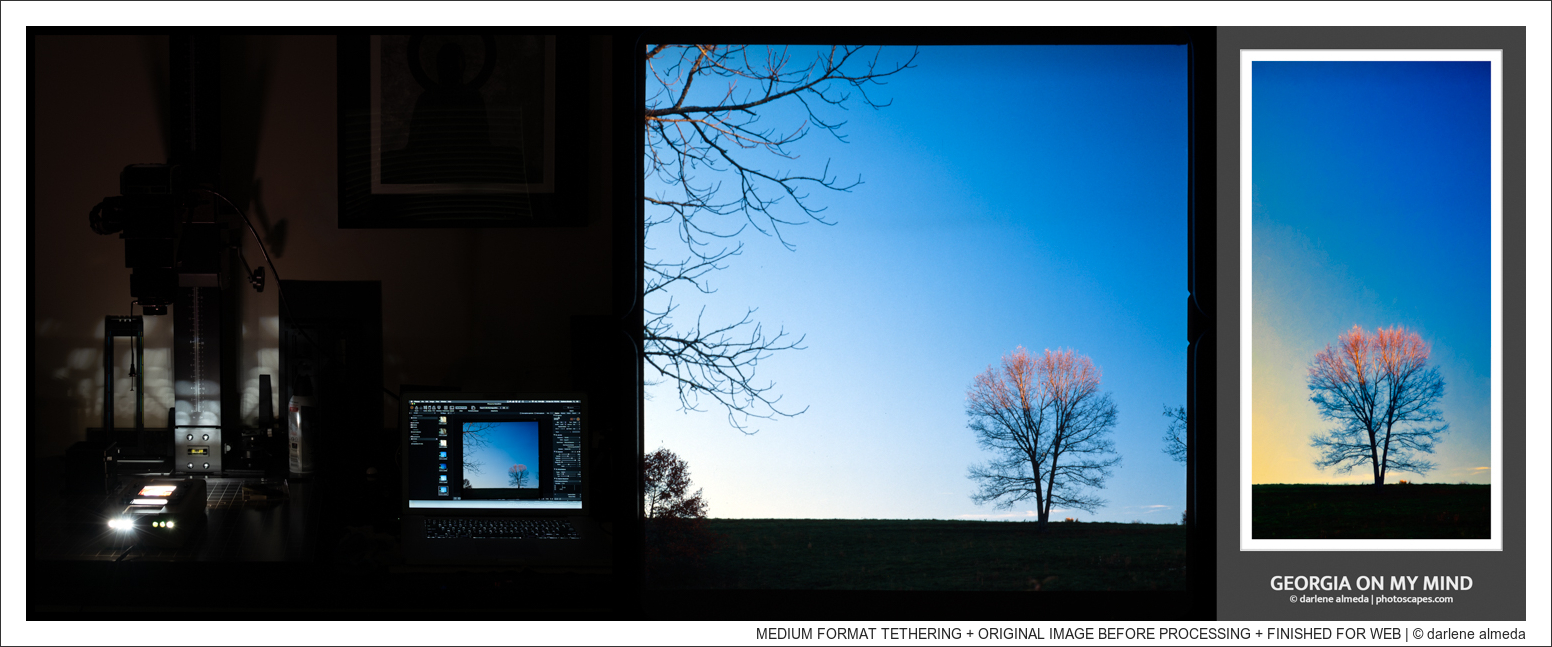

[ MEDIUM FORMAT TETHERING + DIGITIZED BEFORE PROCESSING + FINISHED FOR WEB ]

I recently took part in an online discussion about my approach to digitizing film using a camera—a method I’ve been refining for about ten years. Before transitioning to camera digitization, I relied on scanners. Earlier, during the film era, when my work was destined for magazine publication, the film was sent to print houses for drum scanning. In this post, I’ll share an update on my current process, the insights I’ve gained over the past decade, the equipment I’ve moved on from, and what I continue to use today.

I still shoot film, though not as extensively as I did during my career when it was the only option for photographers. I continue to work with black-and-white film in 6×6, 6×12, 6×17, and 4×5″ formats. While I have color film stored in the freezer, I use it sparingly since digital suits my color work just fine. However, when it comes to black-and-white, I find film superior for the medium. There’s something about the film base that resonates with me—it provides a level of diffusion that complements the type of black-and-white imagery I appreciate.

In contrast, I’ve seen more digital black-and-white images that don’t appeal to me than ones that do. Digital excels in capturing images that demand a level of sharpness that film naturally lacks unless enhanced. Of course, this is all subjective; your perspective may differ.

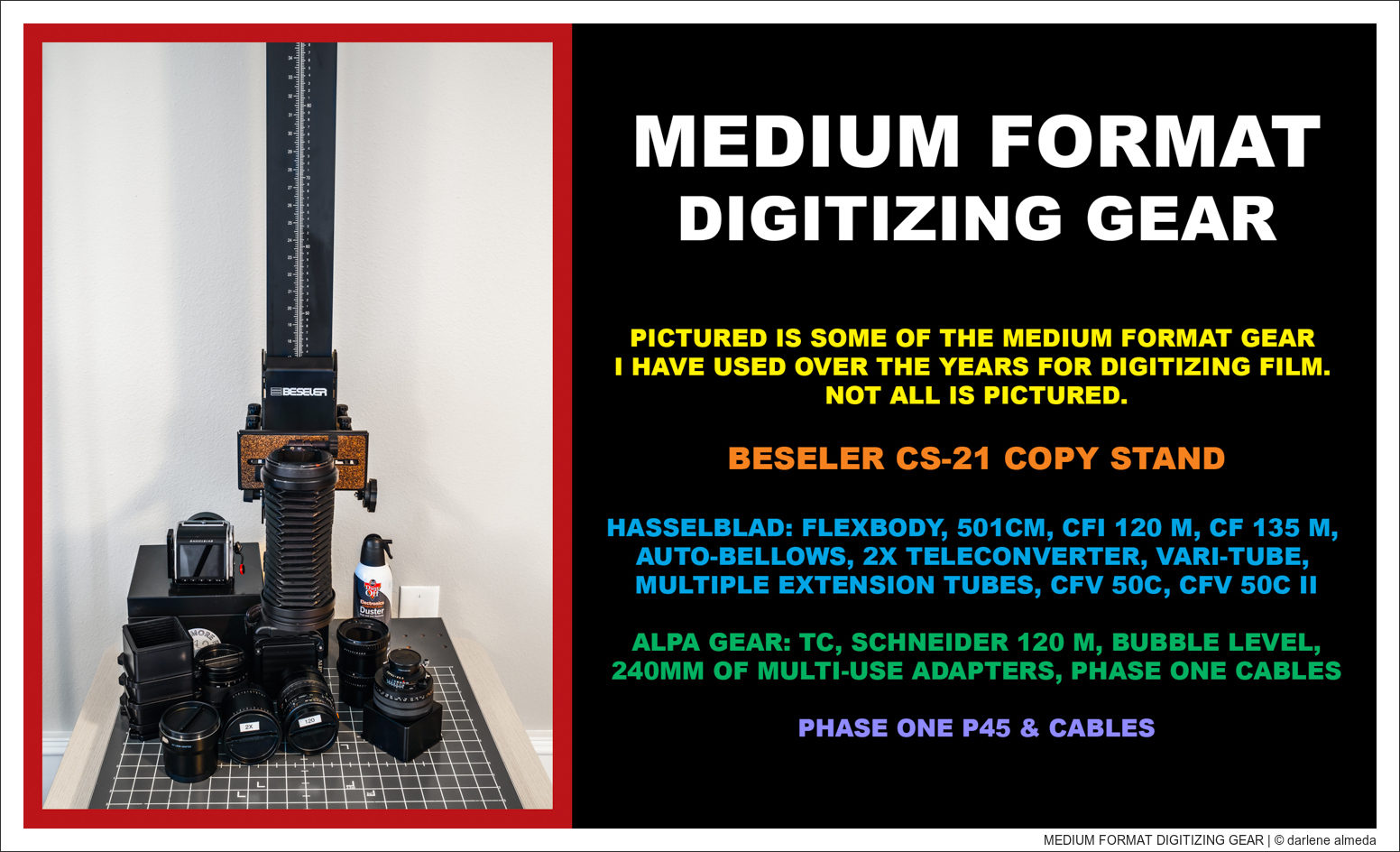

[ MEDIUM FORMAT DIGITIZING GEAR ]

I shoot two digital formats: medium-format on technical cameras and APS-C mirrorless. My current digital backs include the Hasselblad CFV 50c II, which features a 50MP 44×33 CMOS sensor, and the Phase One P45, a 39MP 49×37 CCD back. For APS-C, I use the Fujifilm X-Pro3, X100V, and an IR-converted XE-2. I transitioned away from full-frame Nikon a few years ago when I felt APS-C was “good enough” for my needs. The last full-frame Nikon I used was a D750, provided by the tech college where I was teaching at the time, but I also had a D700 as a personal camera that saw little use.

My commercial photography background has always been in medium and large format. During the film era, while shooting corporate special events and weddings, I relied on several Nikon F3 cameras to serve only as backups. Still, my primary system for portraits and location shoots was always the Hasselblad V system. In the studio, I used various 4×5 cameras over the years for product photography, including Arca Swiss, Calumet (Cambo), Linhof, and Sinar models. For personal 4×5 work, I’ve primarily used Ebony cameras for over 20 years. I tell you all this to set up where I am today with digitizing my film, as I clearly have choices that other photographers may not have.

I began digitizing film with the Nikon D700 in 2012, but I wasn’t thrilled with the results, so I returned to using my medium-format and large-format film scanners. Even so, I appreciated the D700’s speed compared to the slow, noisy, and often tedious scanning process. What I needed was a reliable technique, but back then, there was no information available on what we now call “camera scanning.”

[ 4×5″ FILM BRACKETS + FINISHED IMAGE ]

Over the years, I taught myself to digitize film with a camera, investing in a heavy-duty Beseler CS-21 copy stand capable of supporting my ALPA TC, a Schneider 120mm macro lens, 240mm of spacers, and a P45 tethered to my old MacBook Pro. I repurposed 4×5 enlarger film holders for this setup. I used a basic lightbox, which managed everything, including 6×12 to 6×17 formats under glass—well before any manufacturer offered film holders with a color-corrected lightbox system.

When Hasselblad introduced the first CFV 50c digital back with Live View in 2014, I switched to digitizing with my Hasselblad FlexBody, using macro tubes or bellows as needed alongside the CFi 120mm macro lens. Thankfully, that sturdy copy stand was up to the task of supporting the hefty setup!

I first discovered the Skier Sunray Copy Box through a Facebook group a few years into developing my film digitizing technique, as camera-based digitizing was gradually gaining popularity. Based on strong recommendations, I purchased their early version, and when version 3 came out, it included film holders for every format I needed, including 6×12 and 4×5. This was a game-changer, giving me a complete color-corrected lightbox and film holder setup for all formats except 6×17. (No one makes a setup for 6×17 film, so I continue to use an old Microtek scanner film holder on a color-corrected Kaiser lightbox.)

From there, I began experimenting with exposure bracketing and refining these in Photoshop as layered adjustments to maximize certain negatives’ potential. I also combined image slices, creating stitched images when needed, mastering my technique to suit the unique requirements of each film image. It took about seven years to refine my technique and gather the gear I trust, but with each digitizing session, I’ve grown faster and remain eager to keep learning.

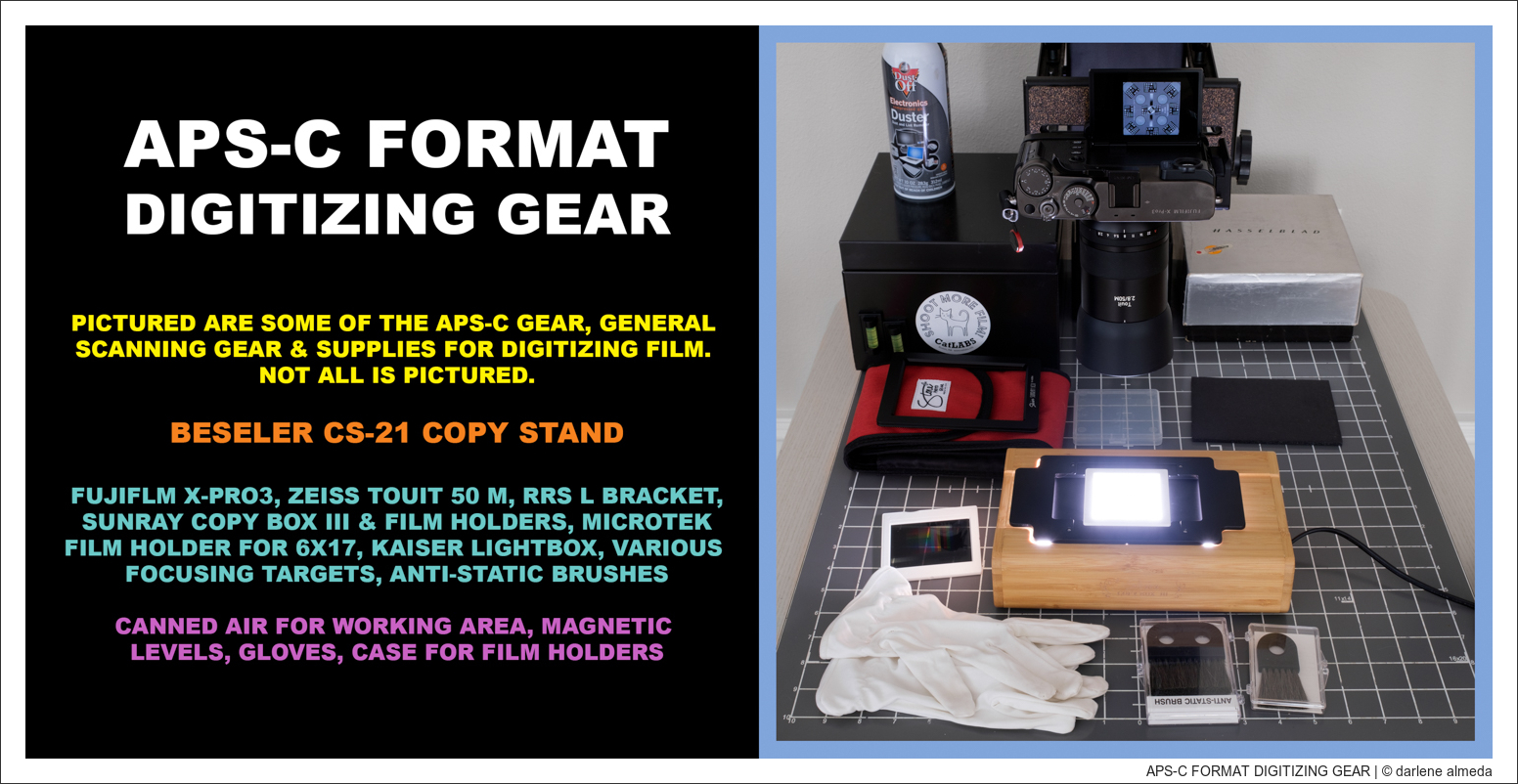

[ APS-C DIGITIZING GEAR ]

When a weather-related incident forced me to pack up my studio, I had to pare down to just the essentials while it was being rebuilt. During this period, I improvised with a small copy stand I found tucked away in my gear closet, setting it up on the kitchen table to continue digitizing and to help cope with the loss of my studio. Using my X-Pro3, I quickly discovered that while medium format gear is fantastic for shooting, it’s not necessarily required for digitizing film. I was still able to create brackets and large image files as needed. This temporary shift to a smaller setup made me realize that simplicity could be just as effective. Plus, I gained the added advantage of using autofocus, which I much prefer.

For the past three years, my APS-C digitizing setup has served me perfectly well. Could my current digital back yield better results? I think not. I’m using the same technique as before with the X-Pro3, and I’m consistently achieving results I’m happy with. Plus, I’d rather not give up autofocus unless absolutely necessary. If the budget were not an issue, I’d invest in a high-megapixel mirrorless camera like a Sony 60MP, paired with a top-tier macro lens, and keep it permanently mounted to my copy stand. It would need excellent autofocus and a forward-facing screen to meet my requirements. Ideally, for me, Fujifilm will release something in their APS-C line that fits the bill in the future.

[ 6×12/6×17 PANO NEGATIVES + LEVELING THE COPY BOX + STITCHED 4×5″ NEGATIVE EXAMPLE ]

Continuing from the online discussion about digitizing film, a fellow photographer mentioned he hasn’t yet matched the quality of his drum scans with camera scanning, though he’s still new to the process. Drum scanners, with their precise methods, can capture subtle details and micro-densities that other scanners, lenses, or sensors might miss. To achieve this fine level of detail, I use exposure bracketing, which enhances the image’s nuanced depth and light quality. While not every film image requires bracketing, for those that do, it’s a valuable step in my post-processing workflow.

In my experience, quality results hinge on solid technique, provided the gear is capable. It’s also worth noting that drum scanning involves a skilled human operator who effectively “post-processes” or tweaks the image during the scan—their expertise results from the time invested in mastering the machine and the process.

[ AUTOFOCUSED SLIDE DIGITIZED WITH APS-C + UNPROCESSED FILE + FINISHED FOR WEB ]

My experience digitizing color negative film is more limited because half of the color films I used in my career were transparency films, where what you see in the slide is what you get when using good technique. For commercial portraits and special event work, I used Kodak VPS III, which is now called Portra. Those film negatives are no longer in my possession, as when I retired from my studio in Atlanta, I either sold the film negatives to the clients or shredded them with a heavy-duty paper shredder. I paid my son, who was in middle school at the time, to handle that after school, and it took him about six months to complete the shredding because it was a huge archive of film.

The reasons for shredding the negatives were two-fold. First, I was retiring from the studio business and relocating, and I didn’t want to store such an extensive film archive. Second, while on vacation in the Florida Keys, I walked into the women’s restroom at a bar and grill and was shocked to see the walls covered in actual professional photos of people and families. Since all of my commercial contracts included a non-disclosure agreement, the idea of someone finding my clients’ films in the trash and using them in such a way was unacceptable; shredding the negatives ensured my clients’ privacy was protected.

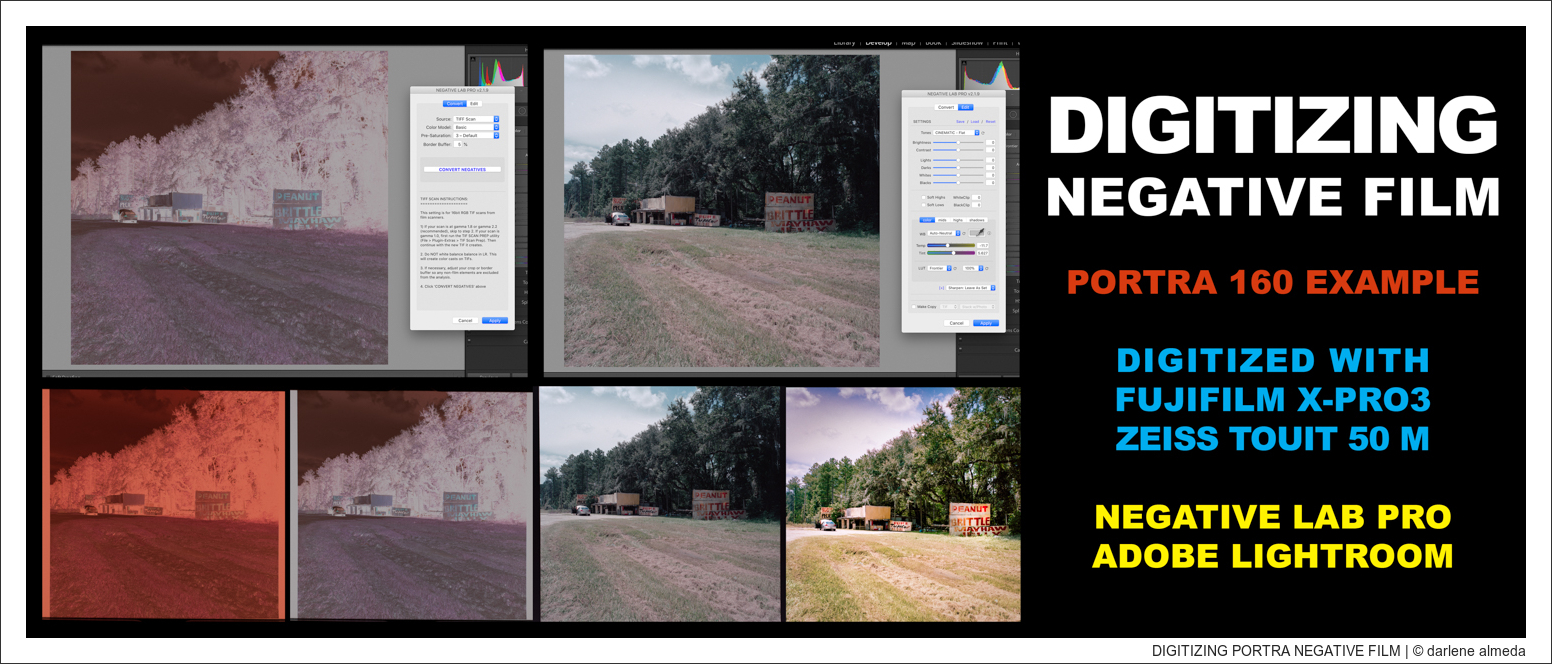

[ DIGITIZING 120 PORTRA WITH NEGATIVE LAB PRO ]

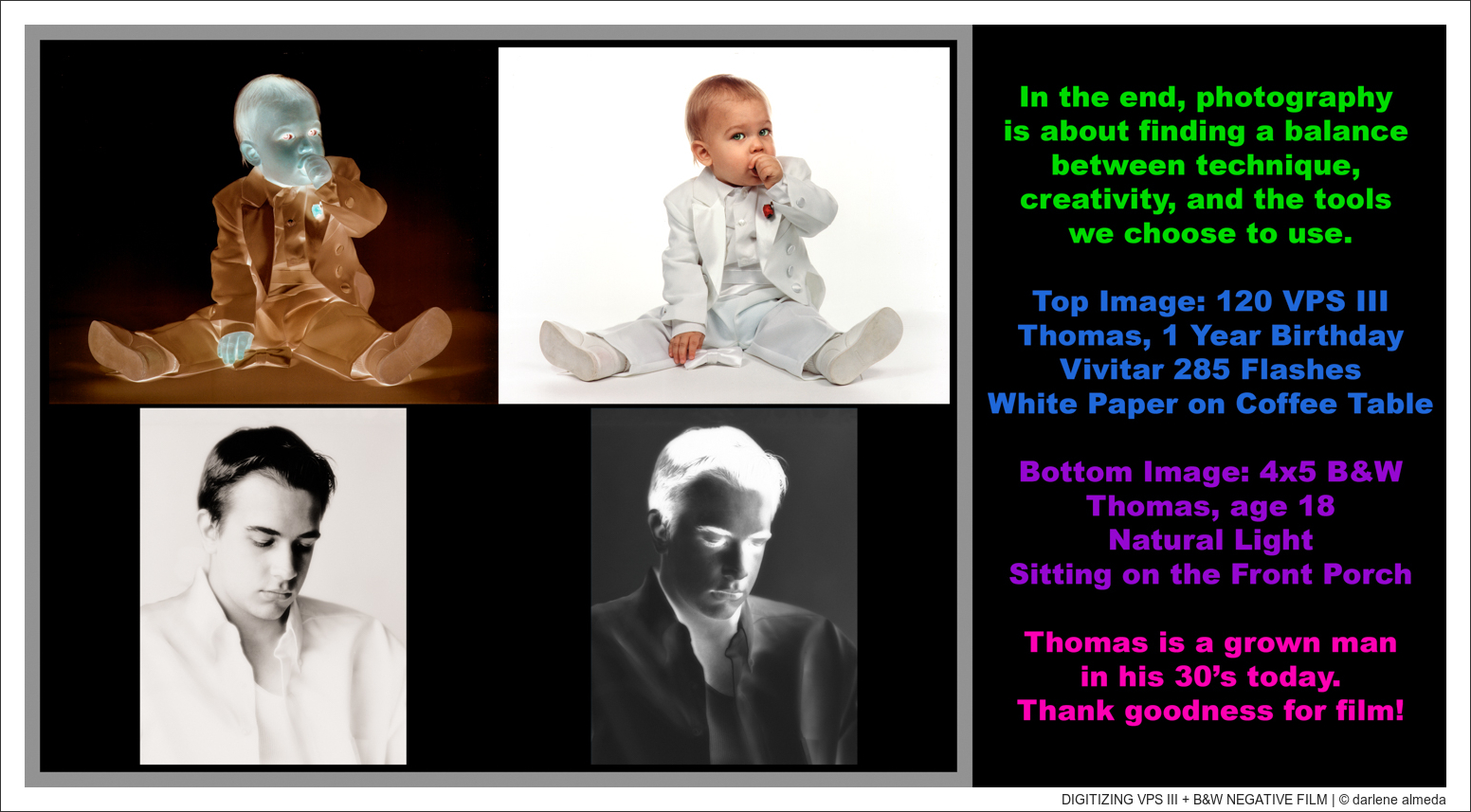

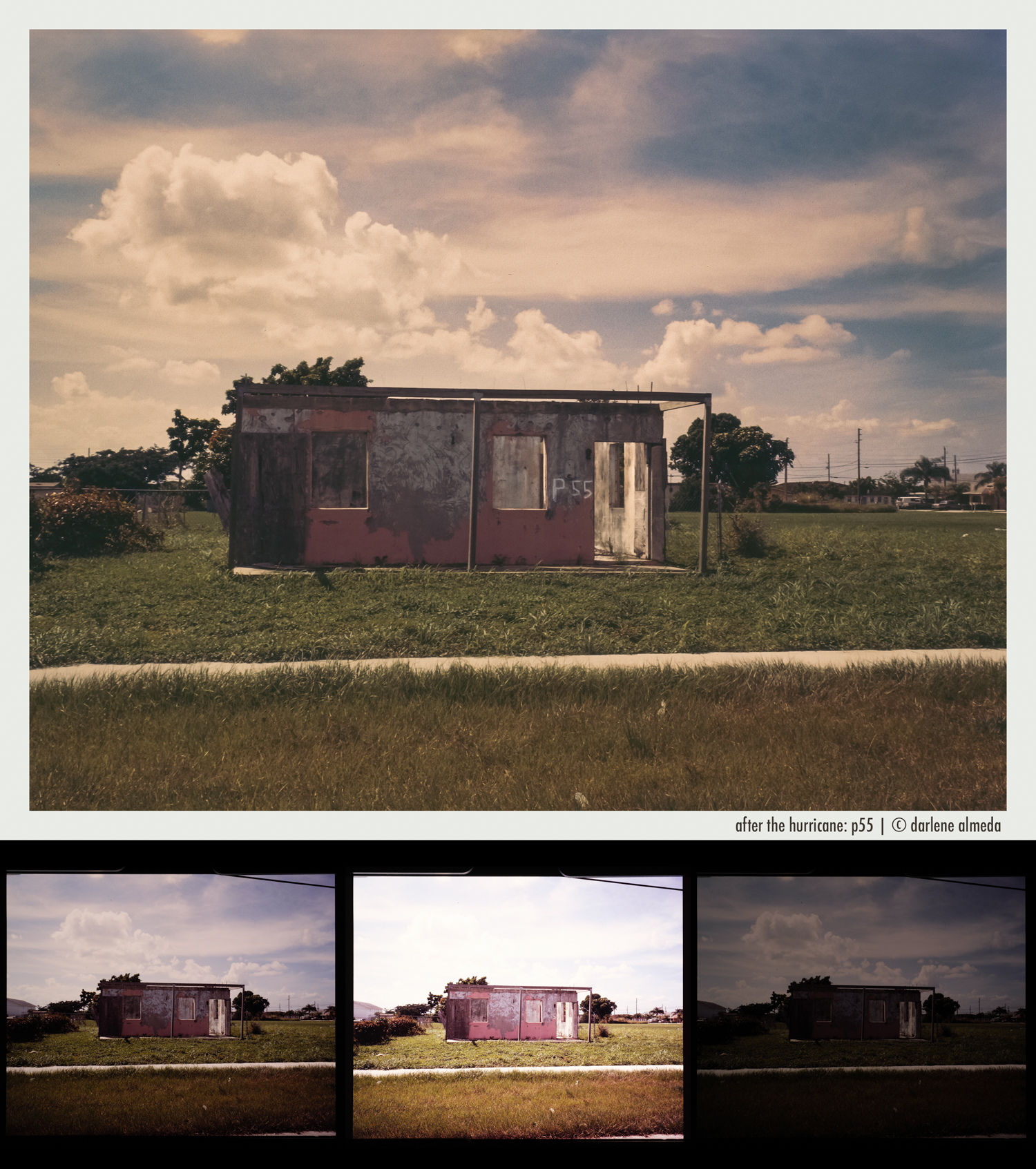

Above is a 120 roll of Portra I shot with my Mamiya 6 that digitized seamlessly. Post-processing in Lightroom was straightforward using the Negative Lab Pro plugin. I have a portrait collection of my son growing up, captured on various films and formats and scanned years ago with a film scanner. Recently, I’ve digitized a few favorites to keep the image files current and to review my technique, which I’ve included below.

Another critical factor in achieving the desired results from digitizing film is post-processing. Although the image originates on film, digitization provides some room for adjustments. However, it doesn’t offer the same flexibility as working with original images shot-as-RAW, where deeper edits are more feasible.

While there’s some room for fine-tuning, it’s a delicate process that can be unforgiving if not handled carefully. I always digitize my files for flat contrast since increasing contrast is easy in post-processing, but high-contrast digitization is irreversible. This is why refining your post-processing skills is so important. The key takeaway is the classic advice: aim to get it right in-camera whenever possible, and for me, I want to start with flat contrast camera scans.

[ DIGITIZING 120 VPS III + 4×5″ B&W FILM + AN ONGOING PROCESS ]

To me, the essence of photography remains rooted in mastering technique. Those who consistently produce great work do so because they’ve honed their skills, whether digitizing film or shooting black-and-white using the Zone System. Good technique is essential for achieving desirable results.

While it’s easy to get distracted by expensive gear or be led down the wrong path, photography is a creative pursuit that requires experimentation to discover what works best for each of us.

Beyond imagination or gear preferences, the fundamental difference between me and another photographer comes down to technique. I’ve invested considerable time refining mine because, ultimately, it’s the blend of effort and passion that truly matters. If you knew me, you’d know my love for photography and the visual arts has shaped my life. Developing your technique and learning which tools to reach for in post-processing takes dedication and practice.

[ EKTACHROME BRACKETTING EXAMPLE – FUJIFILM X-PRO3 ]

Feeling discouraged when your vision hasn’t yet materialized isn’t wasted time—it’s part of the process. Keep pushing forward; you’re honing your skills, and in time, you’ll get there. Those who say they can’t often just stop trying—it’s as simple as that.

In the end, photography is about finding a balance between technique, creativity, and the tools we choose to use. Whether it’s through film or digital, large setups or compact gear, what matters most is our commitment to refining our craft and pushing our creative boundaries. My approach to digitizing film has been shaped by years of experimentation, adaptation, and a willingness to embrace change. By focusing on technique over equipment and passion over perfection, we find our way to creating images that resonate with us and, hopefully, with others.