SHOOTING WITH CREATIVE INTENT

In response to someone who said, “The old, ‘just shoot anything’ to get you going again doesn’t work for me… I just end up wasting time, energy, and money to produce crap,” and added, “If you find the answer, please let me know.”

I get it. But I’d argue that creativity doesn’t come from shooting anything—it comes from seeing something differently.

The two images above were made just minutes apart, using different cameras (Nikon F3 & Hasselblad) and film stocks (Scotch Chrome 1000 & Ektachrome). They have the same model, light, and background. The only change was the prop—and the intent. That’s where creative seeing begins. It’s not about taking random shots; it’s about working with what’s in front of you and practicing the art of seeing in new ways. After all, a camera is just a box that captures your vision, not create it out of thin air.

That’s the difference between documenting and creative seeing.

Documenting verses Creative Seeing

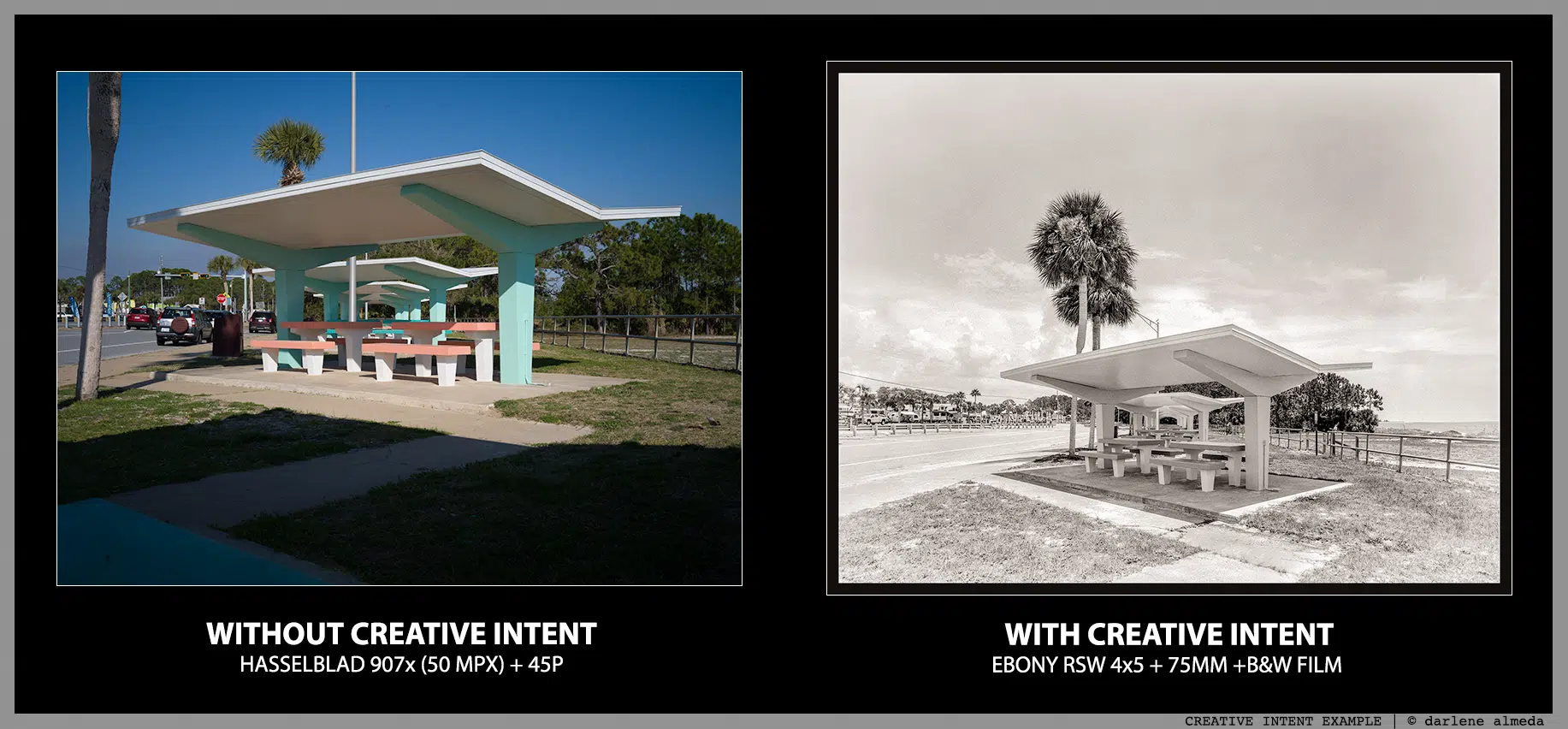

ROADSIDE TREASURE: A CREATIVE INTENT EXAMPLE

Many photographers rely on their cameras simply to document what they see, to record the scene in front of them accurately and clearly. That’s one approach, and it has its value. It preserves a visual inventory: trees, rivers, clouds, ruins. A well-executed photo in this mode often depends on what the environment offers and the photographer’s ability to expose and develop correctly. However, documenting is only one facet of what photography can be.

There’s a different kind of seeing — a creative kind.

Creative seeing isn’t just about what you photograph but how you respond to it. It’s interpretive, emotional, and personal. A bend in the road might feel like longing. A weathered gate might become a symbol of time passing. In this way, the landscape becomes more than scenery — it becomes metaphor, memory, and mood. You’re no longer just preserving what’s there but shaping how it’s felt.

This kind of seeing requires more than technical proficiency. It requires awareness, stillness, and the willingness to be moved by something small or easily missed. In that moment, the camera stops being just a recording device and becomes a means of translation, of revealing the invisible layers beneath the visible world.

I know not everyone will understand this approach, and that’s okay. We each walk our path with photography. Mine happens to be rooted in curiosity, emotion, and the quiet joy of making meaning through the lens. I trust that the work will speak for itself. And if you’re reading this with that same creative urge stirring quietly within you, follow it. You’re not alone.

Sunflowers and Playing Guitar

SUNFLOWER: Ebony 4×5 + 120mm Macro + Polaroid 55P + Handcoloring

If I were to use playing the guitar as an example, it might make a bit more sense.

You buy a guitar and an instruction book. Maybe you pick up a chord encyclopedia, thinking it might be helpful later. You try learning a few chords, then search for music books filled with songs from your youth — little time capsules of heart and memory.

But after a few months, the guitar stays in its case. You feel disappointed. You’ve spent time and money, and all you have to show for it is frustration.

Now, someone else buys the same guitar but takes a different approach. They stick with a structured method that teaches them how to read music, follow the staff, and find the notes. With practice, they can play what’s written. But at first, it sounds mechanical — like a typewriter following commands. The melody is there, but the soul is missing.

Still, they’re on the right path. Given enough time and commitment, they’ll memorize the piece, close their eyes, and begin to play with feeling. That’s when it becomes music.

Anyone can buy a guitar, but not everyone takes the time to learn how to play it. You don’t need the fanciest instrument or a shelf full of books — but you do need a method, and the willingness to practice.

Ask any decent guitarist, and they’ll tell you it takes work before it becomes play. The same is true for photography. Except instead of sound, our art lives in the visual. And the method good photographers develop is seeing.

When was the last time you picked up an art book? Not just photography books, but books about painting, drawing, sculpture — where the artist had to see something in their mind before creating it on the canvas. That’s pre-visualization. That’s learning to see. And that’s a solid path to becoming more than just a documentarian with a camera.

But if that sounds like too much work or not for you, that’s okay, too. Not everyone is meant to love the craft at that level.

Learning to see takes time—like playing an instrument or speaking a new language—but the rewards are deep and lasting. Something shifts when you begin to see with intention, to feel your way through a scene instead of just recording it. Your work becomes more personal, more alive, more you.

So if you’re drawn to photography as more than documentation, keep going. Stay curious. Keep noticing. Trust that your way of seeing is worth developing, because it is.