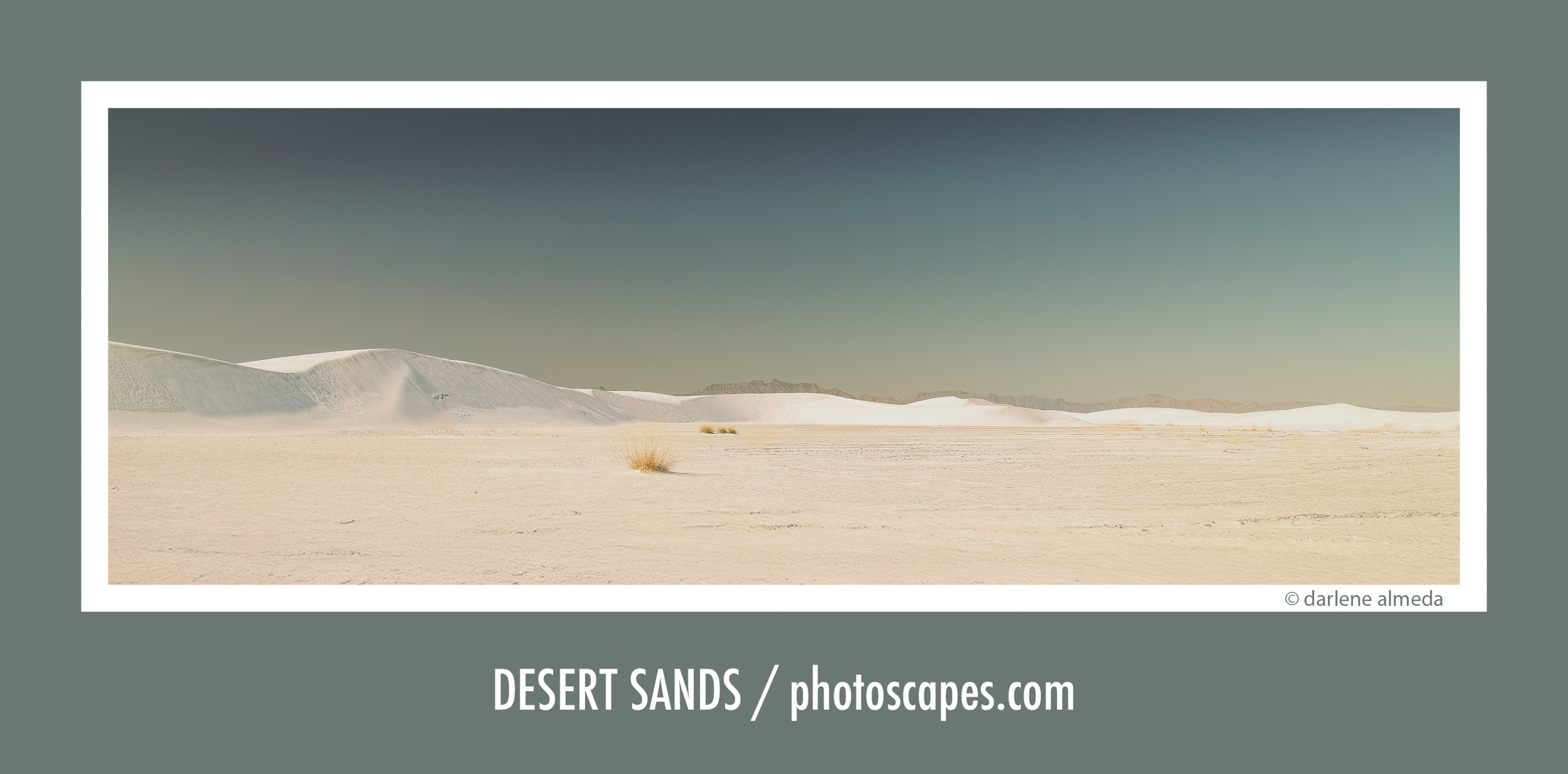

White Sands National Park, Alamogordo, NM

Photographed with one of photography’s quiet marvels.

Some of the most deceptively simple cameras I’ve ever used were the Sigma DP Merrill trio — the DPM1 (19mm/28mm EFOV¹), DPM2 (30mm/45mm EFOV¹), and DPM3 (50mm/75mm EFOV¹). I say deceptively because anyone who has spent time with a Merrill knows that beneath its minimalist exterior lies a complex and demanding machine.

The Foveon sensor inside those cameras was unlike anything else — then or now. When everything aligned, it produced images of extraordinary beauty, rich in depth and tonal nuance. But that word when carries weight. The same sensor could also deliver harsh color smearing, rendering promising photographs unrecoverable in post-processing.

My patience truly unraveled with Sigma Photo Pro, the RAW software required at the time. It was painfully slow, an endurance test for any photographer’s workflow. Combined with sluggish buffer clearing and the occasional image artifacts, my enthusiasm faded until I finally sold the trio, one by one.

Still, when the universe aligned and the DP Merrill delivered a clean, luminous RAW file, the results were breathtaking. To think that such remarkable image quality could come from a small, unassuming black box remains, to this day, one of photography’s quiet marvels. I am grateful to have had the opportunity to experience them.

¹EFOV = equivalent field of view

Sigma DP Merrills 1, 2, 3

What a DP Merrill Camera Offered

The image Desert Sands was created with the DP1 Merrill camera and later cropped to a 6×17 aspect ratio. I wanted to remove some of the sky and foreground to achieve a minimalist composition, something the desert naturally lends itself to.

The desert speaks through wind and silence. Its beauty isn’t loud or immediate, but revealed slowly — through the curve of a dune, the shifting tones of sand, and the distant contours made brilliant by light and shadow. In this photograph, I aimed to convey that stillness — the sensation of being enveloped by light and time, both endless and fleeting.

Standing there, the silence felt alive. The dunes shifted softly in the distance, like memory, while the horizon dissolved into sky. There’s something sacred in that space where form disappears into light, where the earth feels both ancient and newly born.

The Merrill cameras were never easy companions, especially in the desert. Yet, a few images from them carried that unmistakable Foveon character: luminous, dimensional, and worth every ounce of patience they demanded.

Minimalism Up Ahead

In the near future, I’ll be photographing with my Cambo Wide 650 and 6×12 film magazine — this time with a minimalist approach in mind. The project will be captured on black and white film, which I’ll later hand-color.

I can’t quite explain why I find such joy in film, hand-coloring, and hauling around a heavy 4×5 setup just to make 6×12 frames, but I do. Sure, I could use one of my digital cameras, yet there’s something deeply satisfying about working with an old, fully manual film camera that devours film with every shot. It’s simply how I’m wired.

We’ll soon be spending a few days on a not-so-distant island, and I plan to give minimalism a try along the shoreline, with the wind in my face and the waves crashing nearby. I can hear the seagulls as I write.

Maybe it’s time we all pause to appreciate a camera from our past, one that helped shape the photographers we’ve become. For me, I’m celebrating the Merrills. How about you?