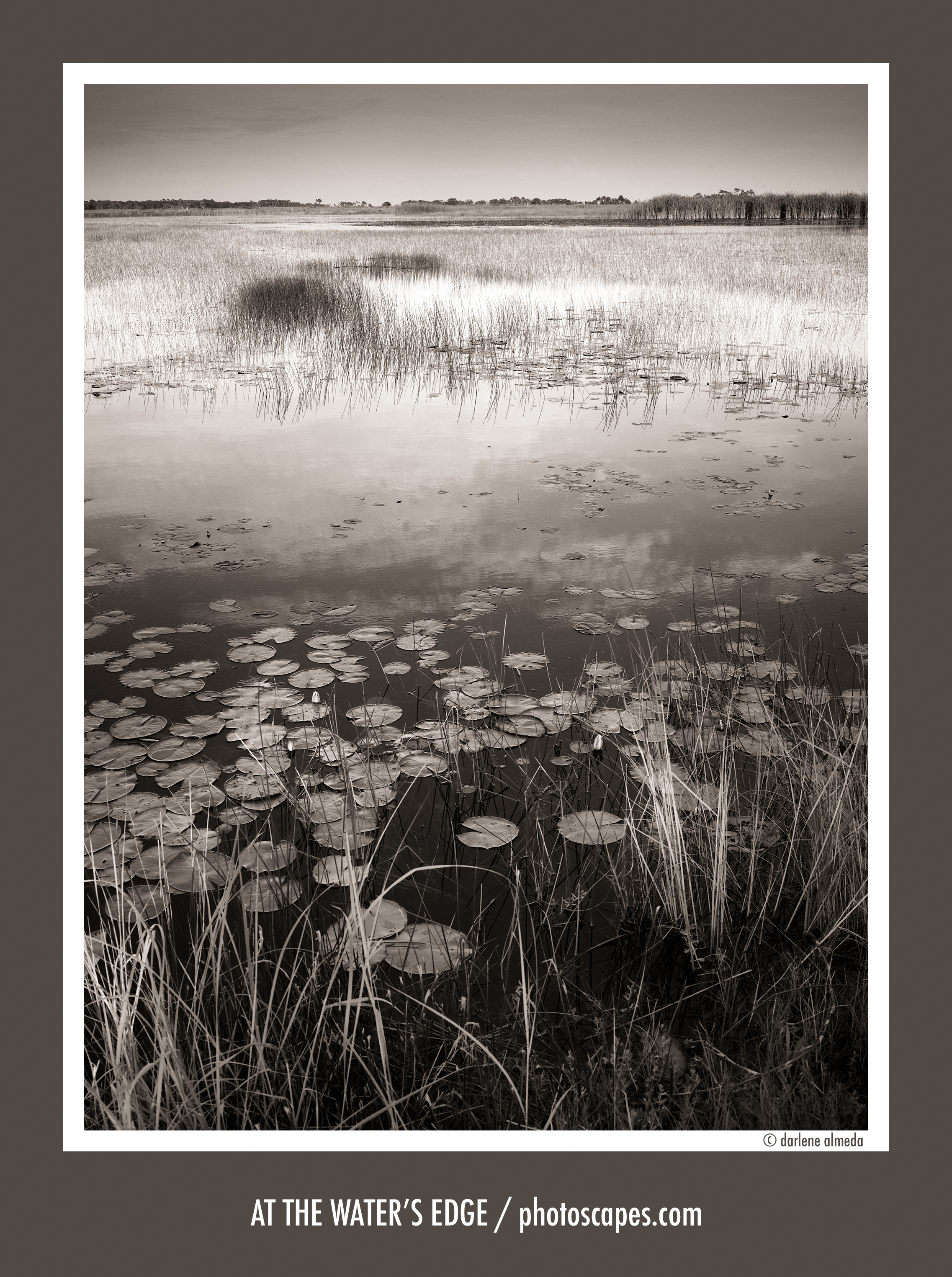

There’s a calm that settles in just before dusk along the marshes of North Florida. The light softens, the wind drops, and the surface of the water turns mirror-smooth. Standing there, it feels as if time pauses — suspended between the weight of the land and the reflection of the sky.

I made At The Water’s Edge during one of those quiet evenings when the world slipped me into a daydream. The air was warm, the grasses still, and a low hum of life surrounded me — frogs, insects, distant herons, and somewhere off to the left, the faint ripple of an alligator easing through the shallows. The air hung heavy with humidity, yet the stillness was beautiful.

The scene felt timeless — like something that could have been photographed a hundred years ago. I wasn’t chasing dramatic light or movement; I was waiting for stillness. The reflection of sky in water, the texture of reeds and lily pads, and the rhythm of tone and form — that’s what drew me in.

Between Film and Digital

My relationship with black-and-white photography began in the darkroom, where light and chemistry shaped every decision. There was a tangible magic to film — an organic softness that felt human, imperfect in the best way. When I later transitioned to digital, I missed that tactile quality. Digital files often looked too sharp, too clinical, as though the light had lost some of its softness.

Over time, I learned how to merge the two worlds. I began approaching digital color captures as though they were film transparencies, imagining how I might have created an internegative to soften contrast or shift tone. That mindset has stayed with me. Every black-and-white conversion I make today begins with the same intention — to interpret, not imitate.

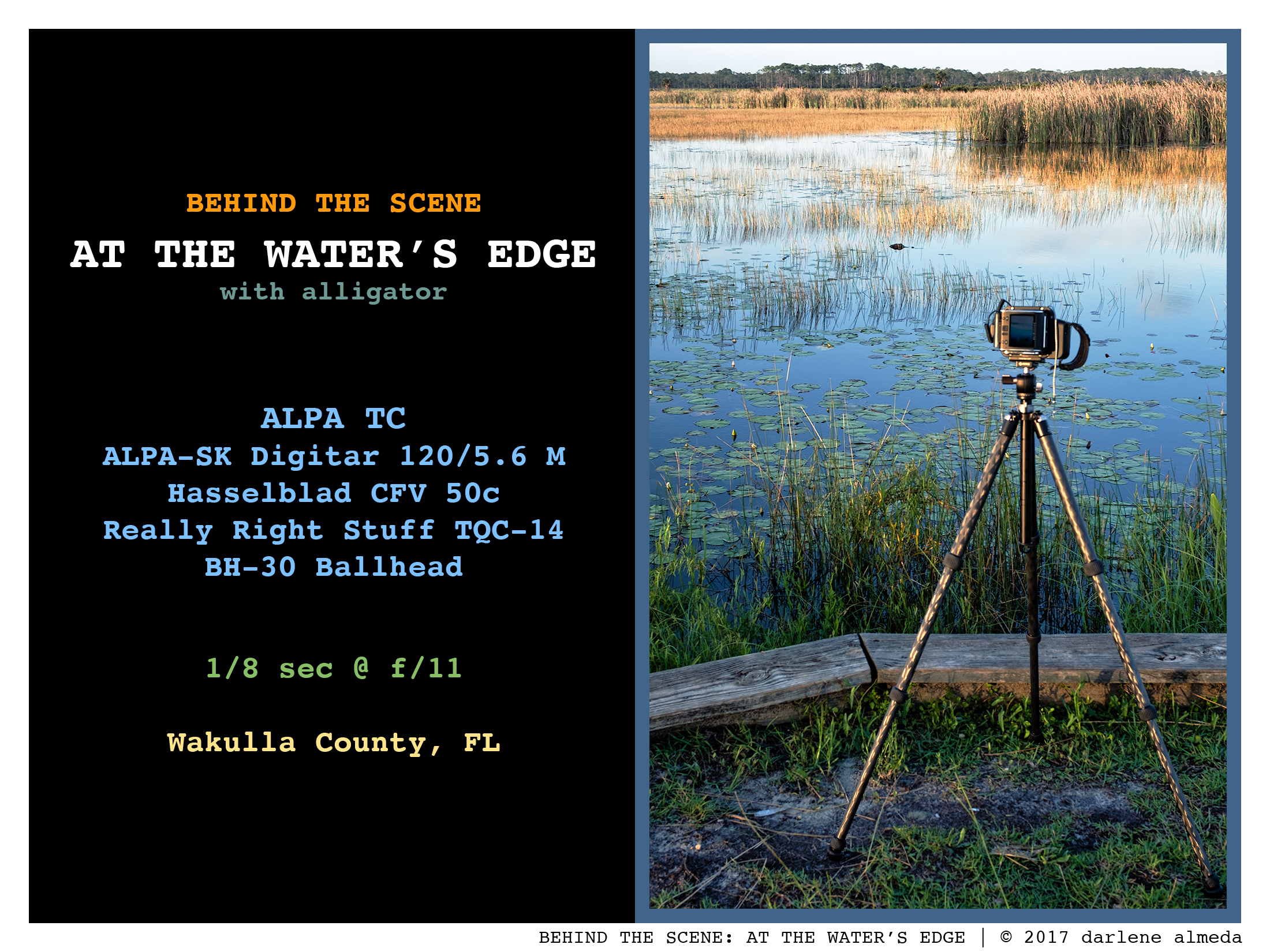

For At The Water’s Edge, I used an ALPA TC camera with a Schneider 120mm f/5.6 M lens and a Hasselblad CFV 50c digital back. The image was processed in NIK Silver Efex, with a subtle tonal adjustment inspired by an old Brooks Jensen method. That small shift added warmth and depth — qualities I associate with film.

The Moment of Capture

I set up my tripod close to the waterline, where the reflections were strongest. Using live view, I focused midway into the frame to balance the delicate reeds in the foreground with the calm expanse beyond. The marsh was quiet except for the distant call of a bird and the faint rustle of wind against the grass.

As the sun began to fade, a thin veil of cloud softened the light. The water turned to glass. For a few fleeting minutes, everything aligned — the symmetry of the sky’s reflection, the whisper of motion in the grasses, the stillness that invites a slower kind of seeing. That’s when I made the exposure.

The resulting image holds what I felt in that moment — serenity wrapped in tension, calm layered over quiet movement.

Reflection

For me, At The Water’s Edge represents more than technique; it’s about returning to the essence of photography — observation, patience, and awareness. The marsh teaches that beauty doesn’t always reveal itself immediately; it waits for those willing to look slowly.

This image bridges my two creative worlds — the precision of digital and the soul of film — and reminds me that photography is as much about feeling as seeing. Each photograph we make is, in some way, a mirror of the self: what we notice, what we linger on, what we choose to preserve.

Author’s Note: I’ve always believed that photography and reflection share the same root — both require stillness. At The Water’s Edge was made in that spirit: part experiment, part meditation, and entirely a reminder that grace is often found in the quiet places where water meets land, and light meets patience.