Why This Lesson Exists

Up to now, Lighting 101 has focused on where to place light—and what it does.

This lesson answers a deeper question:

How do you know what kind of light you want before you turn anything on?

The answer is simple, but not easy:

You learn to see light before you try to create it.

Painters figured this out centuries before photography existed. Photographers who study art aren’t learning history—they’re training perception.

Light Was Solved Before Photography

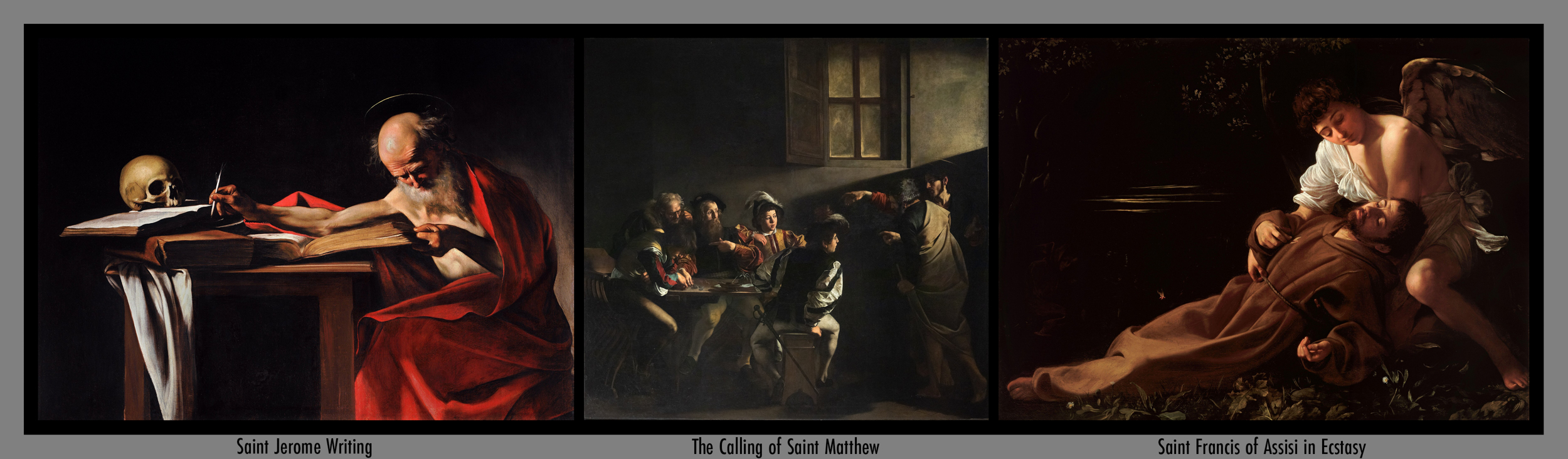

Paintings by Caravaggio (1571-1610)

Long before cameras, painters had to solve the same problems photographers face:

-

How do I describe form?

-

Where should the viewer look first?

-

How do I create mood using light alone?

Artists like Caravaggio answered these questions using light as a selective tool—not as general illumination.

They worked:

-

Without meters

-

Without modifiers

-

Without the safety net of “fix it later”

What they developed was not technique—it was judgment.

Light as a Design Choice (Not Illumination)

In strong paintings, light does not exist to show everything.

It exists to choose.

Light decides:

- What matters

- What recedes

- Where the eye begins and where it rests

This is the same decision photographers make every time they move a light:

- From frontal to angled

- From soft fill to directional key

- From even to selective

Painters teach us a critical truth:

Light is not neutral. It always carries intent.

Once photographers understand this, lighting stops being about coverage and starts being about meaning.

Seeing Shape Before Color

Paintings by Rembrandt (1606-1669)

Artists like Rembrandt understood that form is revealed through transition—not brightness.

Notice in these paintings:

- Faces are sculpted by gradual falloff

- Shadows are dimensional, not empty

- Light wraps and turns rather than stops abruptly

This connects directly to the lighting positions already covered in this series:

- ~45° light describes volume

- ~90° light increases separation and drama

- Small changes in angle radically alter perception

Studying paintings trains photographers to recognize how light turns across surfaces, which is the foundation of expressive lighting.

How to Study a Painting for Light

(A Photographer’s Checklist)

Use this simple checklist when looking at artwork:

- Where is the light coming from?

High? Low? Side? Front? One source or implied multiple? - What does the light touch first?

Face? Hands? Object edge? This is the visual priority. - What falls into shadow—and stays there on purpose?

Shadow is intentional. It is not a mistake. - How soft are the transitions?

Sharp edges suggest drama. Soft transitions suggest volume and calm. - What is not lit—and why?

This often reveals the emotional intent of the image.

Do this enough times, and you stop guessing when lighting photographs.

Exercise → One Photograph

This lesson is not about copying paintings.

It’s about recognition and translation.

Example concept:

- One subject (still life)

- One light

- One clear intention

A Caravaggio-inspired approach might translate to:

- Single directional light

- Strong falloff

- Deep shadow areas allowed to exist

A Rembrandt-style approach might suggest:

- Light placed slightly off-axis

- Controlled shadow with soft transitions

- Emphasis on facial structure or object form

If you can identify:

- Where the light is coming from

- What it emphasizes

- What it ignores

You already know how to light the photograph.

Why This Lesson Is Black & White

For this section of Lighting 101, color is intentionally removed.

Black and white allows photographers to:

- See value relationships clearly

- Focus on shape and structure

- Understand light without distraction

Painters often worked this way too—building value first, color second.

Light always comes before color.

Why This Matters for Creative Growth

Many photographers struggle with lighting because they’re searching for answers in:

- Presets

- Recipes

- Gear solutions

Art teaches something more durable:

- Pattern recognition

- Visual memory

- Confidence in decision-making

When photographers begin recognizing light in paintings, sculpture, and everyday life, lighting stops being a technical problem and becomes a creative choice.

Closing Thought

Learning lighting isn’t about memorizing setups.

It’s about learning to recognize what light does—and choosing it on purpose.

Painters had centuries to figure this out.

Photographers get to borrow that wisdom—if they’re willing to look.

Up Ahead

Next I will share how to use window light with intention—and introduce a secondary light source.